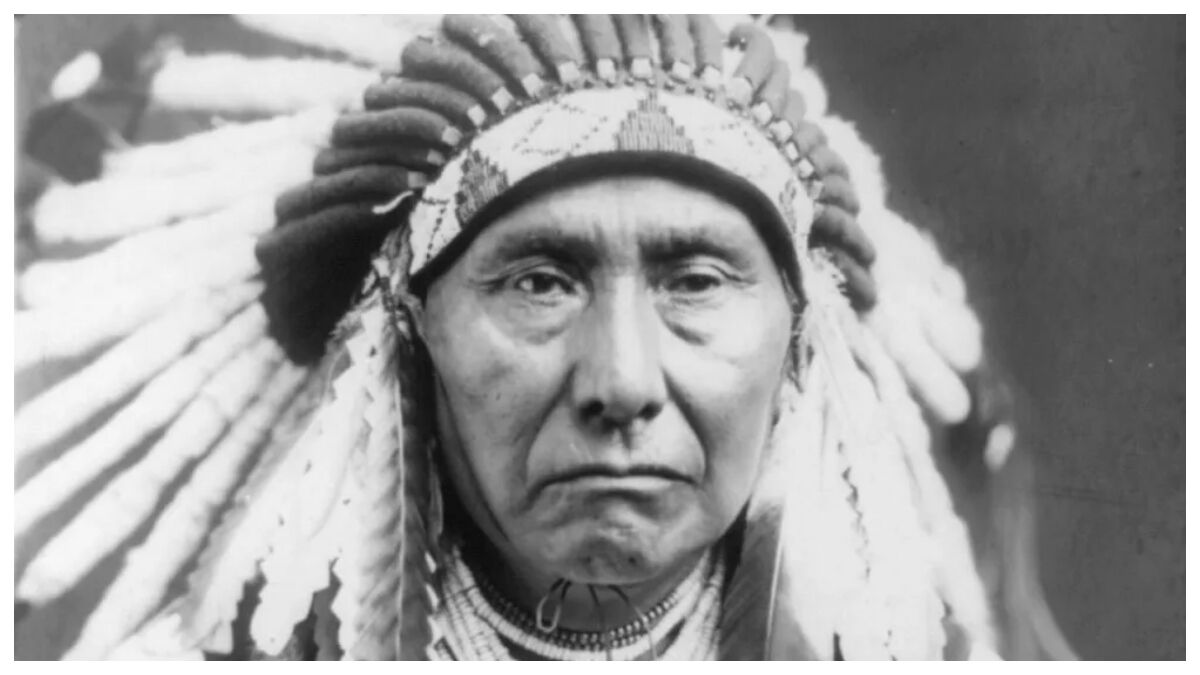

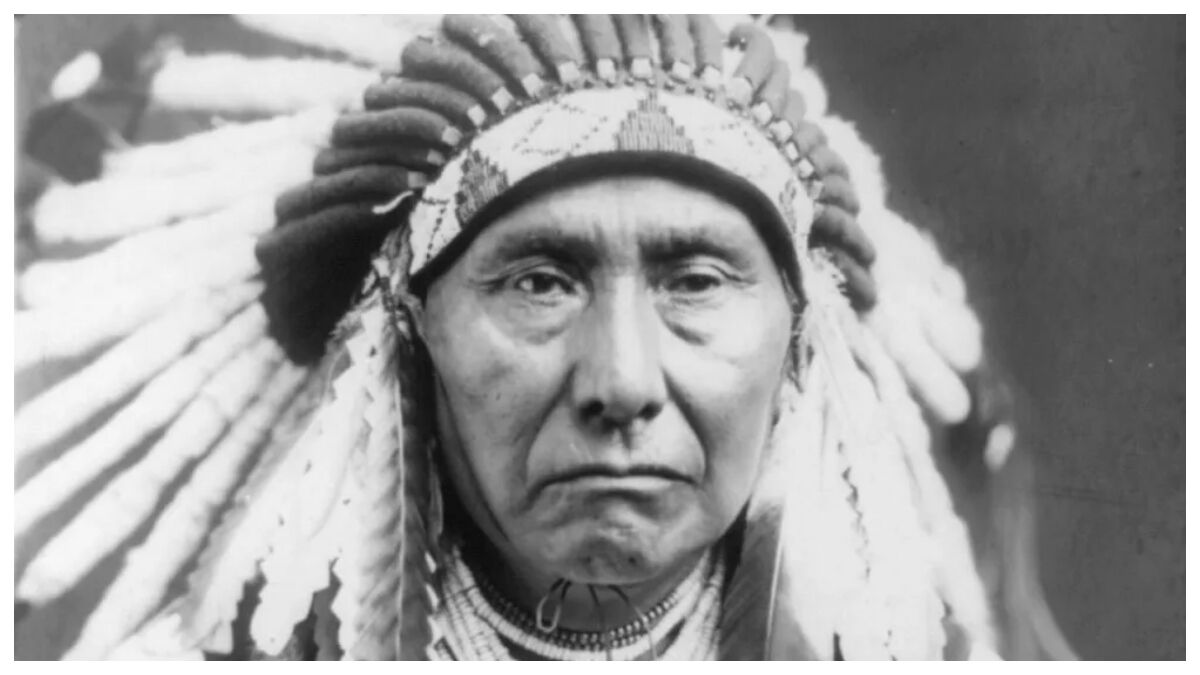

On October 5, 1877, Chief Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it, also known as Chief Joseph, rode on his horse to the foot of a bluff at Bears Paw Mountains in northern Montana, approximately 40 miles from the Canadian border. If he had made it to Canada, he and the Nez Perce people would be free. Instead, his conquerors Col. Nelson A. Miles and General Oliver Otis Howard awaited his surrender. “Draped [in a] blanket about him, and carrying his rifle in the hollow of one arm,” Joseph approached the two men he had been fighting for months “with a quiet pride, not exactly defiance.” Joseph then “held out his rifle in token of submission” to first General Howard and then Col. Miles, who accepted the weapon. An interpreter named Arthur Chapman stepped forward with a pencil and paper pad between Joseph and the US Army officials to record the chief’s surrender. The words Chapman was about to translate became one of the most celebrated speeches in American history.

The following post is by guest contributor Brenden Woldman

The Nez Perce People

Living in the Pacific Northwest along the lower Snake River and the Salmon and Clearwater rivers in modern-day northeastern Oregon, southeastern Washington, and central Idaho, the Nimíipuu tribe, more commonly known as the Nez Perce, had long and peaceful relations with the United States. The Nez Perce made first contact with US officials in 1804 when the Army expedition of Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark came to their lands. The Nez Perce aided and resupplied Lewis and Clark’s expedition to show their hospitality, effectively saving the voyage from failure. In the 1830s, the Nez Perce helped Captain Benjamin Bonneville explore the region and welcomed the Army officer generously.

In 1855, Chief Joseph’s father Chief Tuekakas, or Joseph the Elder, agreed to a treaty negotiation with the United States at Walla Walla. The treaty stipulated that the US would respect the inherent rights of the Nez Perce people and negotiated a settlement that would allow 7.5 million acres of land to be an exclusive reservation for the Nez Perce, which included the Wallowa homeland. However, US officials, settlers, and gold rushers began encroaching on the agreed-upon land once gold was discovered in the region. The federal government called for another treaty council in 1863 to renegotiate the settlement. This time, the terms were far harsher and became known to the Nez Perce as the “Thief Treaty.” The new treaty called for a 90% reduction in reservation size to 750,000 acres and included giving up the entire Wallowa territory.

Joseph the Elder and other Nez Perce chiefs were appalled by the offer. While he and four other chiefs walked out of the negotiations, other Nez Perce leaders agreed to the new treaty, splitting the tribe into those who supported and were against the new deal. When Joseph the Elder began to succumb to illness, he told his son and eventual successor Joseph the Younger some advice when negotiating with the United States. “When you go into council with the white man,” he told the future leader of the Nez Perce, “always remember your country. Do not give it away.” Joseph agreed to his father’s wish. In 1871, Joseph the Elder died. His son was now known as Chief Joseph.

Tensions Begin to Rise

Though relations between some members of the Nez Perce and the US began to sour in the 1860s and 1870s, by 1877, most within the tribe lived in the newly mapped out reservation along the Clearwater River in Western Idaho. They had adopted white American culture, including dressing like the white man, converting to Christianity, and moving past the traditional nomadic lifestyle of their ancestors to instead live as farmers. Still, the bands of Nez Perce, who refused to succumb to the US reservation system, were led by Chief Joseph, who believed they still had sovereign rights to the Wallowa Valley since they had not signed the revised 1863 treaty.

With these small bands of Nez Perce slowly becoming more and more of a nuisance, the US Army sent General Oliver Otis Howard, a Civil War hero for the Union who had lost one arm during the Battle of Seven Pines, to deal with the situation. However, Howard was sympathetic to the Nez Perce’s pleas. Like many within the US Army, including General Philip H. Sheridan, who noted, “We took away [the Native American’s] country and their means of support… and against this they made war. Could anyone expect less?” Howard understood why many Native American tribes, including the Nez Perce, were angry at the US. Howard even wrote to the War Department in 1876 to note the folly in the federal government’s plan to oust the Nez Perce from their lands. “I think it is a great mistake to take from Joseph and his band of Nez Perce’s Indians that valley,” he wrote, “and possibly Congress can be induced to let these really peaceable Indians have this poor valley for their own.”

In 1877, Howard initially wanted to calm tensions by offering to buy the Wallowa land from Joseph and his bands on behalf of the federal government. When Joseph refused, Howard told the chief that he had orders to remove the rebellious Nez Perce bands by force if necessary if they did not relocate to the Lapwai reservation in central Idaho within a month. Joseph did not understand why Howard and the US’s hostility toward him. “My people have always been the friends of the white man,” he told Howard. “Why are you in such a hurry? I cannot get ready to move in thirty days.” “If you let the time run over one day,” General Howard replied, “the soldiers will be there to drive you onto the reservation, and all your cattle and horses outside of the reservation at that time will fall into the hands of the white men.”

Joseph was conflicted but eventually succumbed to Howard’s demands. “I knew I had never sold my country, and that I had no land in Lapwai; but I did not want bloodshed. I did not want my people killed. I did not want anybody killed… I said in my heart that, rather than have war I would give up my country. I would rather give up my father’s grave. I would give up everything rather than have the blood of white men upon the hands of my people.”

Though Joseph capitulated to Howard’s demands for peace, other Nez Perce tribe members continued to disobey the orders. Upon speaking with Howard, Chief Toohoolhoolzote was outraged by the short amount of time the Nez Perce were given. “I am chief!” Toohoolhoolzote exclaimed. “I ask no man to come and tell me anything what I must do. I am chief here!” For his outburst, Howard arrested Toohoolhoolzote, further angering many in the tribe. But Joseph and the other chiefs were desperate for peace and began the long trek to the Laipai reservation. Then, all hell broke loose. In mid-June 1877, a group of young Nez Perce warriors slipped away from their group and killed 18 white settlers as vengeance for how the US had treated them. It was the first time in US-Nez Perce relations had the two been at war with each other.

The Nez Perce War Begins

Howard sent in a unit to squash the minor uprising and wrangle in the rest of the uncooperative Nez Perce at White Bird Canyon. So confident in his forces, Howard wired his superiors that “we will make short work of it.” But to Howard’s surprise, the Nez Perce defeated the attacking US forces, with Chief Joseph observing that some US soldiers “did not hold their position 10 minutes” before retreating. The shocking defeat caused Howard to call for reinforcements. He would not be surprised by the Nez Perce’s ability on the battlefield again.

Following their victory at White Bird Canyon, Joseph and the Nez Perce began a three-month journey attempting to flee US Army forces who were actively pursuing them. Even though the Nez Perce only had a few hundred warriors in their ranks with no formal military training, their natural warrior abilities and the tactics implemented by Chief Looking Glass and Chief White Bird made the small band a mighty fighting force. Though Joseph was not a war chief, he took care of upwards of 500 women, children, and older members of the fleeing tribe.

In early July, the Nez Perce were victorious against the pursuing US at Cottonwood and Clearwater River before Chief Looking Glass began trekking through the Bitterroot Mountains in the Montana territory. Joseph and the other chiefs believed that they would be safe if they could reach their Crow Nation allies in Montana. However, after being cut off by Colonel John Gibbon at the Battle of the Big Hole on August 9-10, the bloody stalemate caused the Nez Perce to redirect themselves by returning to Idaho and then marching toward the Yellowstone Plateau with hopes they could connect with the Crow.

But to Joseph’s surprise, the Crow Nation decided to align with the US and aid in the Army’s pursuit of the Nez Perce. “Many snows the Crows have been our friends,” Joseph remembered retrospectively. “But now, like the Bitterroot Salish, turned enemies. My heart was just like fire.”

The Flight to Canada and the Battle of Bear Paw Mountains

Alone and with no friends in the United States, the Nez Perce decided to flee across the Canadian border to find refuge with famed Lakota chief Sitting Bull. They continued their long trek across the Montana territory throughout the late summer and early autumn months. By late September, Joseph and the Nez Perce had traveled more than 1,500 miles, fought in 17 engagements against the combined force of over 3,000 US soldiers and Native American scouts, and had beaten or evaded capture against every force sent against them. The tactics and tenacity of the Nez Perce earned the tribe respect from their adversaries. John Fitzgerald, an Army surgeon, admitted in a letter that he was “beginning to admire their bravery and endurance in the face of so many well-equipped enemies,” while Colonel Nelson A. Miles wrote to his wife that the “whole Nez Perce movement is unequaled in the history of Indian warfare.”

Unrelenting in their search for freedom and knowing that General Howard’s forces were two days behind them, the Nez Perce stopped to rest at Snake Creek near Bears Paw Mountains, 40 miles from the Canadian border. Unbeknownst to Joseph and the Nez Perce, Col. Miles was just as relentless in his pursuit of them. Leading the 5 th Infantry, the 2 nd and 7 th Cavalry, and Lakota and Cheyenne warriors, Miles and his 450-man force made the brutal 260-mile journey from East Montana to the Bears Paw Mountains in nine days to intercept the Nez Perce. On the morning of September 30, Col. Miles and his forces began attacking the Nez Perce at Bears Paw. Wave after wave of Miles’ forces was beaten back by the Nez Perce. Even after the death of Chief Toohoolhoolzote, the Nez Perce endured.

However, the Nez Perce’s horses, the key for them to make one last escape to the Canadian border, had run off in a panic once the battle was underway. Black Eagle recalled when he realized the horses were gone: “I left going for the horses. I saw our horses not far away. The horses were wise to the shooting and all began to stampede.” Without their means of escape, Joseph and the Nez Perce were surrounded.

“I Will Fight No More Forever”

Surrounded and with the weather turning into a snowstorm, Chief Joseph and his people endured a five-day siege by Miles’ forces. During this time, Chief Looking Glass would perish, and while a few Nez Perce were able to slip away and meet Sitting Bull in Canada, the Lakota chief declared that no force would be sent to rescue them. Negotiating with Col. Miles, Chief Joseph was sent as the leading diplomat to end the siege. Miles was clear in his demands: Joseph that they could return home to the Wallowa Valley the following spring if they surrendered. “My people were divided about surrendering,” Joseph recalled, “but I could not bear to see my wounded men and women suffer any longer. We had lost enough already. Colonel Miles promised that we might return to our own country with what stock we had left. I thought we could start again. I believed Colonel Miles, or I never would have surrendered.”

At approximately 2 pm on October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph rode up and got off his horse, presented his rifle as a token of surrender to General Howard and Colonel Miles, and surrendered. Looking at the two men that had defeated him, he spoke with eloquent pride but with pragmatic duty to his people:

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men, now, who say ’yes’ or ’no’[that is, vote in council]. He who led on the young men [Joseph’s brother, Ollicut] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people–some of them–have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find; maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever!

“Died of a Broken Heart”

The Battle of Bear Paw Mountain marked the end of the Nez Perce War. Joseph and his people were sent on a riverboat to the Dakota territory. Unfortunately, the promises that General Howard and Col. Miles gave to Joseph were quickly broken. Commanding General of the Army William Tecumseh Sherman, the Union Civil War hero whose middle name was named after the famed Shawnee war chief, felt it necessary to keep them away from their homeland. Sherman praised the fighting spirit of the Nez Perce, noting that “The Indians throughout displayed a courage and skill that elicited universal praise… Nevertheless, [the Nez Perce] would not settle down on lands set apart for them… They should never again be allowed to return to Oregon.”

Joseph and the Nez Perce were loaded on a train and sent 2,000 miles from the Wallowa Valley to Oklahoma. Conditions were terrible in the new reservation, and many did not survive the winter. Among the first to perish was an older man named Halahtookit, who was believed to be the half-Native American son of William Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition. The son of the first American who the Nez Perce helped 70 years prior would die tragically on a US-controlled reservation.

Chief Joseph would regret believing in Howard and Miles’ promises. Jaded and cynical, Joseph would admit, “I am tired of talk that comes to nothing. It makes my heart sick when I remember all the good words and broken promises.” Chief Joseph spent the rest of his life living in the reservation system, forever mourning his decision to surrender. On September 21, 1904, Chief Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it, the man known as Joseph, died. He was 64 years old. In his final moments, the white physician who tended to Joseph concluded that the chief of the Nez Perce “died of a broken heart.”